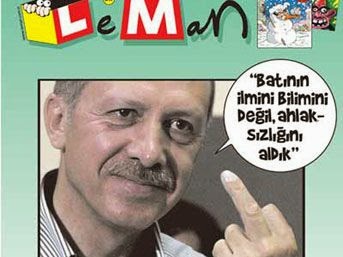

February 23, 2009Last week, the Turkish ministry of Finance fined the Doğan media group 826 million Turkish Liras ($490 million), the result of the state's investigation into the company's taxes. The fine, which is the largest ever assessed a company in Turkey, is larger than the company's entire estimated value. The company has vowed to appeal the ruling, which will cripple the media group if allowed to stand. This news comes in the wake of a series of events taking place in Turkey which, in some ways, are reminiscent of efforts undertaken by the Kremlin in recent years to bring independent media in Russia under state control. Whereas in the case of Russia such efforts have been roundly (and justifiably) criticized in the western media, the increasingly interventionist approach of Turkey's AK Party (whose Turkish initials stand for Justice and Development, or Adalet and Kalkınma) government vis-a-vis the country's independent media has been largely ignored. The Doğan Media Group (DMG) is the owner of some of Turkey's best-known newspapers, including Hürriyet, Milliyet, and Radikal. While the media company was for years viewed as having a generally cozy association with the AK Party (which first came to power in Turkey in 2003), this relationship came to a crashing halt in September of 2008. The cause of the confrontation is widely seen to be the aggressive reporting by newspapers in the DGM with regard to the Deniz Feneri scandal, in which millions of dollars raised by a Turkish charity in Germany is alleged to have found its way into the coffers of the AK Party in Turkey. Turkish Prime Minister Tayyıp Erdoğan, who is the leader of the AK Party, claims that the coverage by DMG newspapers of the scandal represents an attempt by the company to defame the AK Party. However, among many Turkish commentators--especially, but not only, those working for DMG papers--the government's attacks on the DMG constitute an effort by the AK Party to "neuter a bastion of political opposition." This is not the first time such a charge has been leveled at Erdoğan. On December 5, 2007, an organization called Çalık Holding purchased one of the largest media companies in Turkey, ATV-Sabah. The sale of ATV-Sabah, which was overseen by the state in the wake of the previous owner's bankruptcy, was made under extremely suspicious circumstances. Money used by Çalık to make its bid was provided, in part, by sources from Qatar, and in defiance of Turkish law governing such procedures the presence of foreign financing was not mentioned in the company's bid. Also raising eyebrows was the fact that much of Calik's financing came from loans provided by two state-owned banks, whose directors were AK Party appointees. Most noteworthy of all, however, was the fact that just six months earlier the business world had been shocked to learn that Tayyip Erdogan's 26 year-old son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, had been appointed General Manager of Çalık. By December of that year, the Turkish Prime Minister was in the fotunate position of having his own son-in-law manage one of the largest media companies in Turkey, and nobody had even seen it coming. Not only has Erdoğan assessed a crippling tax against one media company and installed his son-in-law at the head of another, but the Prime Minister has also worked to intimidate the media in smaller ways. Since taking office in 2003, the Turkish prime minister has reportedly sued Turkish journalists and cartoonists for character defamation on more than fifty occasions. In early February of this year, Erdogan won a suit against Leman, a popular humor magazine, winning four thousand Turkish lira ($2375) after having sought twenty thousand when the magazine published a photomontage of Erdogan flipping people the finger.

As someone who works not only on Turkey, but also on Russia, I can't help but compare American media coverage of these events to that which focuses upon similar media-muzzling in Russia. If Vladimir Putin personally sued Russian newspapers for character defamation, or if his son-in-law headed a company which came out of nowhere to receive sweetheart state-provided loans in purchasing a major media company in the country, I think the chances are pretty good that we would have heard about it by now. Indeed, if the Turkish government's investigation of the DMG's back taxes sounds eerily familiar to you, it's probably because this maneuver is one which has been used time and again by the Kremlin to silence government critics. As is the case in Russia, in Turkey there is arguably no company large or small that could not be found to have made problematic decisions with regard to the payment of taxes. In both countries, the very decision to closely investigate a company's taxes is pretty much tantamount to a punishment. In the case of the DMG, this means silence. Not only have American correspondents writing on Turkey generally ignored this story, these outlets are in many ways missing what I consider to be one of the major political stories in Turkey today: the AK Party's gradual consolidation of power in Turkey. Having won two majority victories in a row in parliamentary elections in 2003 and 2007, the AK Party is now taking on both the military and the opposition through the Ergenekon trial. In the second posting of this series, I'll talk about the Ergenekon trial and American press coverage of it, and then in the third and final posting of the trilogy I'll look at the newspaper Taraf and its embrace by American observers of Turkey. Since the three postings are related and heavily cross-referenced, I'm putting them together as a sum of three parts. |

Turkish Politics and the News I: A Putinesque Muzzling of the Media

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Darf man ChatGPT fur die Uni nutzen wird an vielen Hochschulen diskutiert. Entscheidend sind Transparenz, Eigenleistung und die Beachtung der jeweiligen Prufungsordnung, damit der Einsatz verantwortungsvoll erfolgt und keine formalen Probleme entstehen.

ReplyDelete