Saturday, February 5, 2022

Thirty years ago this upcoming week, on Feb. 7, 1992, I began a four-month trip that would change my life in several ways.

|

| I was a Copy Consultant |

I had recently graduated from college and, since August of the previous year, had been living in my parents' house in Ann Arbor. I was working two jobs--at Kinko's and delivering furniture--that I'd had in high school. The goal? Saving up money for a trip through central and eastern Europe.

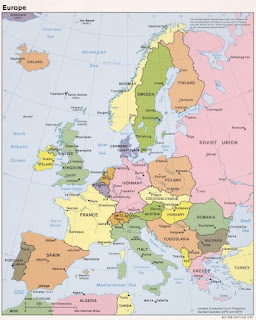

Why did I want to do this? Well, the short answer is that I was interested. I'd been a college student between the years 1987-91 and the revolutions in 1989 had really captured my imagination, as did events taking place at the time in the Soviet Union.

There were also other reasons. My older brother, who had worked as an English teacher for years in Hong Kong, had visited me in Montreal just before I was set to begin my senior year of college. We spent hours walking around town and talking--it had been a few years since we'd seen each other. At some point, my brother began suggesting that I look for work as an English teacher after graduating from college. He'd just traveled through over the Trans-Siberian Express from Beijing to Moscow, and then through Hungary, Croatia, and Slovenia in order to meet up with my parents, who were living in Milan at the time. In his opinion, Hungary seemed like it would be a good place to set up shop, and he'd heard good things about Poland and Czechoslovakia, too (this was the summer of 1990).

I didn't need much convincing. I was already interested in the region and didn't care too much about making money (or getting properly trained), and was excited about the idea of seeing the ex-Warsaw pact firsthand. What I needed was validation, and that's something he provided, as did my parents, when I later talked to them about the idea. Everybody thought it sounded like a good idea, at lease in principle. It kind of depended on what sort of job I could find, especially since I had no training whatsoever in teaching English as a second language.

|

| Thanks, Mom! |

So, I worked for six months at Kinko's and Prisms II furniture and saved money. And then, because I'm an idiot, decided to begin my trip in the first week of February.

It wasn't a well-thought out decision. I didn't prepare well for the weather and was often cold. Actually, if I had done a better job of building a travel wardrobe to suit the climate, the timing of the trip wouldn't have been so bad. But it would have been smarter to go directly to Greece and then leave Italy for the end of my trip. A lot of the low-budget backpacker type of accommodation that I was seeking was closed in Italy, and during the course of the early days of my trip--mid-February in northern Italy--I was pretty miserable.

In particular, I was beating myself up for spending so much money in Italy. I wasn't eating well, either, because I was so desperate to not go over budget. This meant a lot of wandering around in the rain in soggy, poorly-selected clothing. I became a little bit obsessed by the fact that I was somehow "failing" at traveling.

About ten days in I just broke down and sobbed into my pillow one night. I felt so frustrated by how much everything cost, and was really down on myself for spending too much money. But then I had something of an epiphany, if you can call something so obvious and late-coming by that name. I realized that I didn't really need to prove anything to anyone, and that I should just spend what I need in order to stay warm, well-fed, well-rested and happy because, after all, I was on vacation.

|

| The Acropolis, Athens, March 1992. |

Originally, I hadn't even planned on going to Turkey. But a lot of people had talked up Istanbul, in particular, and had good things to say about Turkey in general. So, I decided to check out Edirne and Istanbul for ten days before heading north to Bulgaria.

During the course of my stay in Istanbul, I was offered a job in a completely random-seeing way, something which I discuss in more detail here. Long story short, I left Istanbul after a week with a job offer at Marmara University, then spent a few days in Edirne before crossing the border at Kapıkule just south of Svilengrad (is it a sevilen (beloved) grad (city)?

I ended up spending two months traveling through eastern and Central Europe, eventually making my way all the way up to Gdansk. It was a great experience, and I was really thrilled to be in what I still thought of as the ex-Warsaw Pact.

This was why I had not immediately said yes to the job offer in Turkey. I really preferred the idea of living in a smaller, quieter town and, frankly, a place with a more European feel. So, as I traveled, I always kept an eye open for language schools. Walking through, say, Brno, I would see a school, walk in, talk to someone in administration, and try to get an idea of how willing they were to hire someone with a degree in English literature but no training, certificate, or experience in teaching English as a second language.

|

| Telč, Czechoslovakia, in April 1992 |

|

| Kids on the train between Istanbul and Edirne, 1992. They'd been in Istanbul to take an exam for entry into elite,low-cost high schools. |

|

| At Marmara University, March of 1992. |

I felt wanted in a way that I didn't encounter elsewhere. I was this very ordinary recent college graduate, and yet I was treated as if I were somebody special. It was my first taste of what living in Turkey would (mostly) be like.

|

| Downtown Bucharest, near the university |

Toward the end of September, about a week or so before I was to fly to Istanbul, I stopped by Kinko's to pick up my last paycheck. Working that night was a guy whose name I no longer recall, but he was a graduate student at Eastern Michigan University who was notorious for being a little difficult to work with. Typically he manned the 11-7 graveyard shift overnight. I think he was studying English Literature.

"So when are you leaving?" he asked me.

"Next week" I said.

"Well all I can say," he said as I was about to walk out the door, "is that I'm glad it's you and not me that's heading off to live in some third-world shithole of a country."

This never happens to me, but for once in my life I actually had a perfect response to this kind of behavior, not because I was particularly quick-thinking or anything. Rather, the answer felt completely natural, even reflexive.

"Me too," I said.

*

I would end up living in Turkey for seven years before heading back to the US in 1999 to begin graduate school. Prior to living in Turkey it never would have occurred to me to go to graduate school and become a history professor. My experiences in Turkey between 1992 and 1999

A few takeaways:

a) My plans during the course of my travels. I ended up visiting places that weren't on my original itinerary, and was offered a job in one of these places, changing the trajectory of my life. I go back a lot, too, for research and personal reasons. Until the pandemic, there had been just one year--2002--when I did not spend at least part of the calendar year in Turkey.

b) If any one of ten different things hadn't happened they way that they had, I likely never would have found myself interviewing for a job at Marmara University. But more important than any single one of these developments was the broader fact that I felted wanted in Turkey. I think that, if I had spent, say, a month in Turkey, I would have ended up meeting multiple people who would have suggested that I live there and work as an English teacher. There were English-language schools on every block in some neighborhoods, so perhaps I would have gone in and started asking questions in the manner that I would later do in Eastern Europe. So, rather than the individual coincidences and curious happenings that eventually helped me stumble into a job in Turkey, what mattered most, I think, was the fact that so many people gave me the impression that they would love to have me live there. And that's hardly a unique experience. Both the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey have long histories of taking in losers and renegades from the outside world and finding some way of making use of them.

c) Family encouragement mattered a lot. My parents had taken us, as a family, to France on two six-month sabbaticals in 1975 and 1983. Learning foreign languages and seeing other countries were activities that they both supported. My brother was an important example, and the fact that he had suggested Eastern Europe made it a lot easier for me to think about actually doing something like this without feeling stupid. Because it's not necessarily easy--or at least it wasn't for me-- to imagine traveling and living abroad if you don't know someone else who has done it.

And my parents let me live at home for six months so I could save money, in addition to buying the ticket and special-ordering the guidebook that I needed. When I told them in June about the job offer in Turkey, they were supportive, and encouraged me to take the job.

It's almost as if they were trying to get me out of the house.

But that's a good thing, I think. The first student who ever visited my office hours at Montana State was a young woman, very smart, whose principle ambition was to go back to the small town in Montana where she had grown up and teach history at the high school she had attended. We chatted for a while, and she told me she was graduating soon. I asked her if she had ever considered living abroad. I'm not sure she understood at first what I was talking about, but after a few seconds she pointed out the window of my office, which looks onto the Wilson Hall courtyard, and said "this is the most beautiful place on earth. Why would someone want to live anywhere else?"

The mountains that surround us in Montana are truly gorgeous. I spend hours sitting at a table--where I am now sitting--looking out onto the Bridgers. In the summer, I sit out on the patio, listening to baseball on the radio and staring at those mountains.

They're captivating, for sure, but the mountains can also hem us in. So, that's one of the reasons why I like my job at Montana State: I feel like I have a perspective on the value of learning foreign languages and seeing the world that maybe my students don't always get from their other professors. I also try to encourage my students to do something immediately after college other than graduate school and, to the extent possible, use their time right after college doing something that adds value to their future marketability, whether it be as a potential graduate student or otherwise.

The trip I began 30 years ago has never really ended.

Travels like this can take us in unexpected directions, so here's to having the chance to take more of them in the not-too-distant future.

***

More commentary, photos, and links can be found in the Borderlands Lounge.

No comments:

Post a Comment