Monday, March 27, 2023

This morning I was minding my business as usual at the Borderlands Lodge when, fresh from emerging from a mid-morning sauna I happened to notice the snowy residue of footprints on my front walk.

Well, who could that be? I wondered.

|

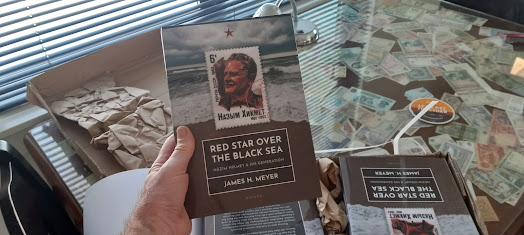

| It feels great to see this baby in print |

After seven and a half years of working on this project, it's pretty amazing to finally hold the book in my hands.

And what about you? Any interest in getting a copy of your own? If you're still on the fence, maybe checking out the prologue (sans footnotes) below will help you decide.

In the meantime, please forgive these tears of joy...

Prologue

Tears of Joy

It was an early Sunday morning—June 17, 1951—and Nâzım Hikmet was awakening into darkness. Turkey’s best-known poet was fleeing his country, heading north to Bulgaria. At forty-nine years of age, Nâzım was making one more reach beyond his grasp, seeking to escape from the prison that Turkey had become for him. His once reddish-blond locks were showing hints of grey and Nâzım’s face was now creased with age, but still he was seeking to add chapters to his life. Nâzım Hikmet would remain trapped inside no longer.

As he would later recount to his debriefers in Romania, Nâzım had started this day well before dawn. Creeping out of his home on the Anatolian (or “Asian”) side of Istanbul, he had walked down to the main road and flagged a taxi. Arriving at the pre- arranged spot, he exited the car and made his way down to the Bosphorus, the turquoise saltwater strait that divides Istanbul—and Turkey—between continental Europe and Asia.2 The Bosphorus would this morning serve as the highway that Nâzım would take in his escape, just as he had done when he had fled British-occupied Istanbul at the age of nineteen. This time, Nâzım’s brother-in-law Refik was spiriting him out of the country on a small Chris-Craft motorboat.

On the face of it, their plan was insane. The Black Sea is notorious for its rough waves and strong current. Yet Nâzım and Refik, the husband of Nâzım’s younger half- sister Melda, were proposing something even more challenging than just riding the potentially treacherous seas on such a small craft. They were also hoping to somehow make their way past the patrols of Turkish navy and coast guard vessels and enter the territorial waters of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, some 130 miles away. The idea was for them to do an end-around past the Iron Curtain, enabling Nâzım to go and live as a free man, he hoped, in the USSR or elsewhere in the Eastern Bloc.

It wasn’t going to be easy. In recent years, the Turkish–Bulgarian border had emerged as a potential Cold War flash point, with the two countries positioned in opposite camps across a burgeoning superpower divide. The frontier between Turkey and Bulgaria was now a death-zone for those attempting to cross illegally. For an idea of what could go wrong, Nâzım needed to look no further than at the example of his fellow leftist writer Sabahattin Ali. In March of 1948 the author of Madonna in a Fur Coat paid a guide to lead him from Kırklareli, Turkey to Burgaz, Bulgaria. Weeks passed, however, and Ali never showed up on the Bulgarian side of the border. On April 16, a Turkish shepherd discovered his decomposing body near the frontier. Someone had rained down blows upon the bespectacled novelist’s head, crushing Sabahattin Ali’s skull with a bat.

Riding the choppy tide of the Black Sea toward Bulgaria, Nâzım and Refik noticed that a ship had appeared in the distance. Getting closer, the brothers-in-law could see that it was a Romanian cargo vessel called the Plekhanov. As was the case with Bulgaria, Romania was an ally of the USSR, which meant that boarding the Plekhanov could conceivably be just as useful to Nâzım as traveling all the way into Bulgarian waters.

After a brief conversation, Nâzım and Refik decided to audible. Refik changed course and the Chris-Craft slowly approached the Plekhanov, with the brothers-in- law now waving excitedly at the ship’s surprised crewmembers. Refik endeavored to steer closer to the ship while Nâzım shouted up several more times to the crew in Russian and French. The little motorboat was pummeled by the waves that were churned up by the much larger vessel.

They began to perceive signs of progress. The ship’s crewmembers cut the Plekhanov’s engines, making it easier for them to hear what Nâzım was saying. But meanwhile, time was passing. If the ship’s crew didn’t take Nâzım, the brothers-in-law would still have a long journey ahead of them.

But Nâzım was in luck, if that’s how it can be described. The previous year, he had been the subject of an international, and largely Eastern Bloc-driven, campaign demanding his release from prison in Turkey. For this reason, Nâzım was relatively well-known in Eastern Europe. The crew of the Plekhanov recognized him, eventually, and came to realize what he wanted from them. After an extended delay while the ship’s captain radioed back to Bucharest to explain that someone claiming to be the famous communist poet Nâzım Hikmet was asking to be let on board, at last a rope ladder was lowered down to the motorboat.

Nâzım turned to Refik and kissed him farewell on both cheeks, Turkish-style. The 49-year-old poet climbed the ladder up toward the deck of the cargo ship looming far above. Refik turned the Chris-Craft around and headed back toward Istanbul. He would never see his brother-in-law again.

*

The next several days were busy ones for Nâzım. First, the Plekhanov transported him to the Black Sea port of Constanța, Romania. After two days in Constanța, Nâzım was taken to Bucharest, where he was visited by a doctor and finally given some fresh clothing to wear. He had only brought what he had been wearing during the escape, not wishing to attract extra attention should he and Refik be stopped by Turkish authorities.

Nâzım’s handlers in Bucharest could not help but notice that the Turkish poet had been deeply affected by the tumultuous events of the previous few days. He had left his wife, infant son, and all of his close friends and family behind in Istanbul, along with his in-progress writings. The new life that he was escaping into, moreover, was at this time still difficult to predict. Despite the fact that he had spent more than fourteen years in Turkish prisons, Nâzım’s reputation in Moscow was far from sterling. His plight underscored the potential lethality of Cold War-era border-crossing. Could it be that Nâzım had escaped from a Turkish frying pan only to jump into a Stalinist fire?

In Bucharest, the officers responsible for looking after Nâzım had noticed their charge’s anxiety. “His nerves are always tense,” read one report to Moscow, “and due to his agitation he is unable to hold back his tears.” Nâzım, however, told his minders not to worry. The uncontrolled rivulets streaming down his cheeks were nothing more, he assured them, than “tears of joy.”

More photos, commentary, and links can be found, comme toujours, in the Borderlands Lounge.

***

Are you a Turk across empires? Order your copy at the OUP website or on Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment