Friday, May 19, 2023

Well, the results of the first round of balloting are in, and it's not looking good for the opposition.

I can't say I'm surprised. While the economy in Turkey has been terrible, this election was largely a referendum on President Tayyip Erdoğan. In a country that is broadly divided regarding their opinions of Erdoğan, people aren't going to turn their backs on him just for the hell of it. They needed a good reason to vote differently this time.

|

| Four-time electoral loser Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu once again faces off against 21-year incumbent Tayyip Erdoğan |

What they got instead was Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, a decent man who in the first round of the campaign made real efforts to appeal to people's better instincts, as opposed to exploiting their resentments in the style of his opponent.

But the resentments that many in Turkey have long held against the Republican People's Party (CHP) are real enough that, 100 years after the founding of the Turkish Republic, roughly half the country cannot bring itself to vote for Atatürk's party.

This would all be quite disadvantageous for anyone running against Erdoğan, but choosing Kılıçdaroğlu as the united opposition candidate still probably wasn't the greatest idea. As CHP party leader he has now led his party to middling results in five straight parliamentary elections, with the CHP always garnering between 20 and 26% in these contests. Running as the presidential candidate representing an "alliance" ticket he did somewhat better, but Kılıçdaroğlu still has too much ground to make up in too little time. Turkish opposition parties choose 3-time general election loser Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu as their unified candidate.

I guess Neil Kinnock was unavailable. https://t.co/ibDSKMFTdr

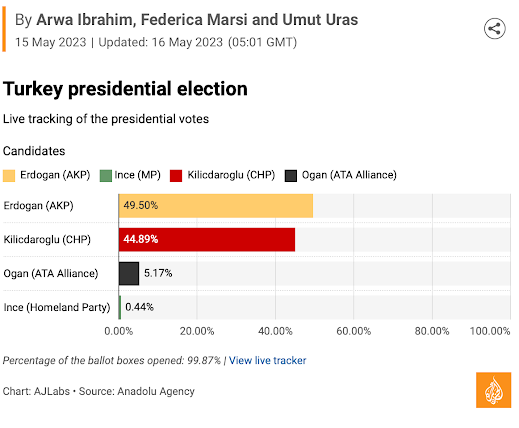

With Turkey now heading toward a second round of presidential balloting on May 28, it seems pretty much like a foregone conclusion that Erdoğan, who received just under the 50% necessary to win, will be re-elected as president. He only needs to pick up 0.51% of the vote.

The Roots of Tayyip Erdoğan

The race between Erdoğan and Kılıçdaroğlu has repeatedly been cast as a stark choice between opposites. Tayyip Erdoğan is rightly criticized for the increasingly authoritarian nature of Turkish politics, while Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu is viewed as a force for returning democracy to Turkey.

Yet it is worth remembering that Mr. Erdoğan was himself initially celebrated as a reform figure when he first came to power in 2002. Less than a year after 9/11 and the beginning of the international war on Islamic terrorism, Turkey had elected “an Islamic politician who favors democratic pluralism.”

So what changed? How is it that this one-time champion of reform developed into an autocrat? For insights into Mr. Erdoğan’s metamorphosis, a brief discussion of the career of one of his predecessors is instructive.

On May 27, 1960, soldiers in Ankara arrested Adnan Menderes, the Prime Minister of Turkey. Born in 1899, Menderes had been a longtime member of the CHP, which had ruled Turkey since the country’s establishment in 1923. In 1946, Menderes and three of his CHP colleagues in parliament founded an opposition party, calling themselves the Democrats. While the Democrats were cheated out of winning that year, they would cruise to a commanding victory in 1950, earning an electoral majority that they would easily repeat in 1954 and 1957. Yet in May of 1960 his government was overthrown in a military takeover, the first in Turkey’s history. On September 17, 1961, Menderes was executed.

What ultimately doomed Adnan Menderes and his Democratic Party was an institutional problem that the country has yet to solve: authoritarian-friendly constitutions. No matter what democratic inclinations Menderes and his colleagues may have initially entertained upon taking office, the constitution they were working under was a holdover from 1924, written one year prior to Turkey’s transition into a one-party state.

When Menderes’ Democrats came to power in 1950, they soon found that, with their parliamentary majority, they could do virtually anything they wanted. There were no checks and balances. A government whose leaders had suffered through four years in opposition now began to abuse its power. Starting in 1955, authorities in Ankara undertook a series of campaigns against their perceived adversaries, especially journalists, judges, university professors, and civil servants. Menderes’ government also sought to whip up mobs to attack Greek citizens of Turkey in retaliation for Greek provocations against Turks in Cyprus. In a famous incident taking place in early April of 1960, military troops were ordered to prevent CHP opposition leader and former Prime Minister and President İsmet İnönü from giving a speech. The incident horrified the country’s junior officer corps, and within two months Menderes’ political career would be over.

The National Unity Committee (NUC), which took power after the coup, prioritized the writing of a new constitution. The new document, which was formally adopted in 1961, was created specifically with the goal in mind of preventing a return to the monopoly of power wielded by the CHP in 1923-1950 and the Democrats after that. Unlike its predecessor, Turkey’s constitution of 1961 guaranteed rights to speech, association, and other freedoms that had been absent from its predecessor. The constitution of 1961 was not perfect, but, from the perspective of individual rights, it was by far the best one Turkey has ever had.

Turkey’s current constitution was produced in 1982, following a second military takeover that occurred on September 12, 1980. This time, the military leaders (not junior officers) who took power decided that there was altogether too much freedom in Turkey. The new constitution watered down most of the language pertaining to rights and freedoms, rendering them virtually meaningless through the employment of various caveats and conditions.

In Turkey today it is legal for politicians to sue journalists over “insulting” coverage, a tool of repression that Erdoğan has utilized literally thousands of times. The crime of “offending state leaders” is also punishable by fine and/or prison. The mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu, was sentenced in 2022 to more than two years in prison for “insulting electoral officials,” in a move that seemed calculated to keep the popular mayor out of the presidential race. The charge of “insulting Turkishness” has most often been used to crack down on Kurdish rights organizations, but has also been employed on two occasions as a means of harassing the Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk. And none of this even begins to address the various ways in which Erdoğan and the AKP have employed branches of the Turkish state to serve their electoral interests.

But guess what? Erdoğan didn’t invent these tactics. Indeed, Turkey’s current president himself spent four months in prison in 1999 after publicly reading a speech in which he quoted lines from a poem by Ziya Gökalp, one of Turkey’s best-known intellectual figures. The crime? “Provoking religious hatred,” a cudgel that was commonly used in the 1990s against Islamically-oriented political figures like Mr. Erdoğan.

Erdoğan’s prison sentence was intended to end his political career, as there was a law at the time banning anyone with a prison record from serving in parliament. When Mr. Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002, that law was rescinded.

|

| Tayyip Erdoğan knows a thing or two about being on the receiving end of Turkish justice |

Where did Tayyip Erdoğan learn to behave in the manner that he does? Who taught him that it was okay to jail and intimidate his critics and political adversaries?

The roots of Tayyip Erdoğan’s authoritarianism, most of which is perfectly legal under Turkish law, are without question intimately tied to Turkey’s present-day constitution. But they run much deeper than that. Authoritarian-friendly constitutions have been baked into Turkey’s political DNA since the country’s establishment in 1923.

It is tempting to see Tayyip Erdoğan, who has built a political career out of bringing Islam back into the public sphere, as the antithesis of Turkey’s radically secular founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. But more than anything else, Turkey’s current president is a product of the political system that Atatürk created, and its republic.

***

Also see: Posts about Turkey

***

Are you a Turk across empires? Order your copy of my first book at the OUP website or on Amazon.

More photos, commentary, and links can be found, comme toujours, in the Borderlands Lounge.

No comments:

Post a Comment