Saturday, March 5, 2022

What an odious and sickening week this has been. It's starting to look pretty clear that Vladimir Putin is determined to punish Ukraine, regardless of the cost. No matter what happens in the long run, the goal right now is to make Ukraine, and Ukrainians, pay a terrible price for not knuckling under.

|

| Putin winning more hearts and minds in Kharkiv |

Even if Russia were to stop shelling Ukrainian cities and power plants right now, it would take years for Ukraine to recover from what has been done so far. And much more damage will be inflicted on the country and its citizens, I think, before this comes to an end.

Crazy or Foolish?

People keep asking: what does Putin want? It's a question I've grappled with in this blog on a number of occasions.

|

| People don't fly planes into buildings simply due to "rage" and "hate." |

I'm someone who typically tries to find the logic in other people's actions. Too often with respect to the parts of the world I work on (Russia and the Middle East), there is a tendency, in the US and elsewhere, to write off behavior we don't understand as simply "crazy" or "stupid," or else ascribe it to people's feelings or emotions.

This can be quite self-serving, too. Remember when W. told us that the US was attacked on 9/11 not because of anything to do with American policymaking in the Middle East, but rather because the attackers "hated democracy?"

But people--and yes, even non-Americans--tend to do things for reasons that, at least in their own minds, make sense in some rational way, rather than simply as a means of expressing emotion. So, I try to understand as best I can why people do the things they do, rather than just put them on the psychologist's couch.

I've always considered Putin a calculating individual, not a madman. Unlike the politicians the Kremlin supports in other countries, Putin is not a blustering, impulsive fool. He's someone who, in my opinion, has typically shown a fairly steady approach to achieving his objectives. The manner in which Russia was able to annex the Crimea without firing a shot in 2014 is an example of what I would describe as a very efficient use of blunt power.

At the present moment, however, I can't honestly say that Putin is following a plan that seems rational. In this case, his behavior might be, to some extent, a reflection of the fact that he's been living in a power bubble for the past twenty-three years. This is what Bill Simmons long ago described as the "I'm Keith Hernandez" syndrome, one that might also apply to the leader of the Russian Federation.

It does seem that Putin is starting to take all of this personally, that he's going out of his way to make Kyiv, and citizens of Ukraine, pay a terrible price for not immediately bowing to his will.

Stuck in the Middle

I don't find it at all surprising that the Russian army is experiencing difficulties in Ukraine--frankly, that's been about the easiest thing to predict during this crisis. What Russia is doing will only seem like a success if Ukraine gives up and foreswears pursuing any closer ties with the European Union or NATO. But for as long as the government in Kyiv holds out and refuses to capitulate, Moscow will remain in a difficult position. Russia can destroy Ukraine, but I don't think they can defeat the Ukrainians for as long as the government in Kyiv is willing to continue absorbing this punishment.

And frankly, the rest of the former Soviet bloc is watching, too. What Putin is doing isn't just about discouraging countries like Ukraine and Georgia from developing closer connections with the West. It's also about sending a message to the leaders of countries like Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan. None of those countries are currently pursing closer ties with NATO or the EU--and the Kremlin wants to make sure that this remains the case.

So, the strategy right now is to pummel the Ukrainian government, and ordinary citizens of Ukraine, into submission. But what if they don't submit?

Russia can't occupy all of Ukraine, and the Russian military isn't even trying to advance on the western regions of the country. I don't want to seem like a cheerleader for war--rooting on Ukrainians, from the safety of Montana, to risk their lives fighting the Russian Army--but I do think that the more deeply Russian forces get drawn into Ukraine, the worse it will ultimately be for Moscow and Putin.De-Modernizing Russia

I found it interesting that the Kremlin has banned Facebook and Twitter in the country, afraid that the country's citizens will disseminate information from abroad.

There once was a time when Putin presented Russia as an alternative form of modernity, one that didn't have to be western-driven. His popularity in Russia--genuine, in many instances--derives from the fact that he has been able to create a more stable society, something that even democratically-minded Russians appreciated after the chaos and economic privation of the Gorbachev and Yeltsin years.

Putin, like many rulers before him, has dedicated himself to modernizing his country in every way but one: politically. Over the past twenty-odd years, Russians have become much more prosperous, better-traveled, and more worldly than they were in the 1990s. Public infrastructure in Russia--and not only in the capital cities--is exponentially better than it was when Putin came into office. The country's health care system, which was in tatters in the 1990s, actually provides quality service to many people now. Life is a lot better in Russia, from a material perspective, and probably from a mental-health perspective as well.

The thinking, of course, is that all of these improvements to people's lives will just make them grateful to their leaders. And sure, that's something that happens. But all of these improvements also tend to increase people's expectations and, eventually, their demands as well.

|

| Russia in 1905: Not everyone was just grateful for the changes Nicholas II had brought |

|

| Workers' dormitory in pre-revolutionary Russia |

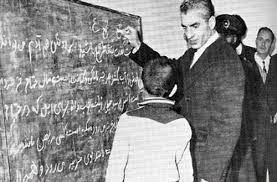

Iran under the Shah is another example of this type of regime. Following the nationalization of the oil industry in the 1960s and spikes in the price of petroleum in the 60s and 70s, the regime in Tehran was flush with cash. The Shah's family stole a lot of that money, but oil revenue was also, at times, spent on things like roads, hospitals, and scholarships for young Iranians to go study engineering in France and the United States.

Did Iranians--who had become more worldly and better-educated than any previous generation in their country--just sit back and feel grateful to the Shah for investing in the social transformation of their society? Of course not. Their demands grew. The Shah had created his own opposition.

The opposition to Putin in Russia is not large. It seems to be composed mainly of middle-class types in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and to some extent in other cities. Some people in the opposition come from a tradition of dissidence, but many others who are critical of Putin today are, in part, a product of the stability and development that the last two decades under Putin have brought to Russia.

That's always been part of the deal: Russians gave up, bit by bit, many of the democratic liberties that had developed under Gorbachev and Yeltsin. In exchange, they--some of them-- have become more prosperous, better-traveled, and more worldly.

Contrary to whatever stereotypes people might have, it's not as if Russians simply love authoritarian leaders. They put up with Putin because he has managed to provide for them. So, what happens when someone who has staked his reputation upon competence, stability, and prosperity leads his country into economic turmoil and a military quagmire? What happens when a self-styled modernizer cuts off information from the rest of the world? Russians didn't sign up to live in North Korea, or Kazakhstan. No wonder the Kremlin is terrified of its own citizens learning that their country is actually fighting a "war," and not a "special military operation." Increasingly, the Russian president is starting to look like nothing more than a malevolent bungler.

*

One last point, however, one that supersedes everything: we are, after all, at just the beginning of this. Remember what things were like when we were only one week into the pandemic? A lot changed over time, and that will be the case with this as well.

***

Also see:

More Thoughts Re Ukraine and NATO

Looking for the Long-Term in Putin's Moves

Moscow Recognizes Two Breakaway Republics: Why do this?

The Monroe Doctrine, Putin, and Post-Soviet Space: Don't Muddy the Waters

***

No comments:

Post a Comment